| Premiere | 8 June 1995 |

| Venue | George Fairfax Studio, Victorian Arts Centre, Melbourne |

DAZE OF OUR LIVES was a visual theatre interpretation of the work of Melbourne cartoonist Mary Leunig. 1

Leunig’s published drawings - There’s No Place Like Home (Penguin 1985), A Piece of Cake (Penguin 1985), and One Big Happy Family (1992), collect her darkly witty commentary on domestic life. Their unusual and slightly disturbing look at motherhood, housework, family life, alienation and fantasies was the stimulus for the style and the story of the play.

Staged through gestural movement and animated design, Handspan described the production as 'a bittersweet monument to domestic terror and the poetry of the everyday.' 2

The Play

DAZE OF OUR LIVES was directed by Annie Wylie, who also co-wrote the play with Katy Bowman. It was based on several creative development periods during 1994 with Handspan performers, and consultations with Leunig to ensure that interpretation of her drawings remained as a close as possible to their original intention. Leunig claimed that:

Watching Handspan make theatre, their creative process, their own interpretations of my work ... by taking liberties and not confining themselves to what I may have 'meant' by a single drawing, the artists of the company have taken the work to a new level which is innovative and inspiring.

In the Director's Notes Annie Wylie wrote:

Each one of Mary Leunig's drawings is bubbling with comment, narrative and action, all of which is a godsend to a company like Handspan, whose work it is to let the universal language of images speak to the hearts and minds of audiences.

Despite this enthusiasm, the writers found that creating a play from preconceived illustrations was a more difficult process than they had anticipated. The work was originally envisaged a performance using only articulated images, props and body-costume puppets manipulated in black theatre to bring Leunig’s cartoons to life on stage. As its development evolved however, dramatisation of the cartoon moments centred on its pivotal housewife character which became an actor's role, created by Julie Forsyth. As planned from the outset, the play nevertheless had no spoken text or dialogue and was accompanied throughout by percussionist Peter Neville’s soundtrack.

In a preshow interview for the Melbourne premiere season, Annie Wylie discussed the evolution of the play's central housewife character:

Working this way is really arse-about for us because it's taking images and then working back. Normally what we take is a notion or a story and then pull images out of that. Staging the drawings was actually quite easy - creating some sort of drama out of that was the really difficult part. There were so many drawings to choose from, great pictures creating miniature stories, but finding a way to link all that and have a character develop was the tricky part ... There was no way for the audience to access any of the humanity of the piece unless we did have a central character''

'She' or 'Her' became the universal housewife whose world came alive as her domestic objects embroiled her in chaos that was by turn hilarious, poignant and darkly frightening. Julie explained how she developed the role:

It's everyone's black world and everyone's fantasy world and my function in the piece is to be that human element that can filter, can comment and have a sense of irony about the piece, of being in an environment that seems to be closing in. How this person is able to detach herself and make a comment on what is happening will in many ways undercut what can seemingly be a black moment.

Performer Julie Forsyth as She builds a determination and self-reliance while negotiating her way through both puppetry and props, and and does so with a vulnerability earmarked by both confusion and resolution. She is a full, honest character, neither saint or martyr, and as such holds the audience interest while negotiating life in the suburban '90s.

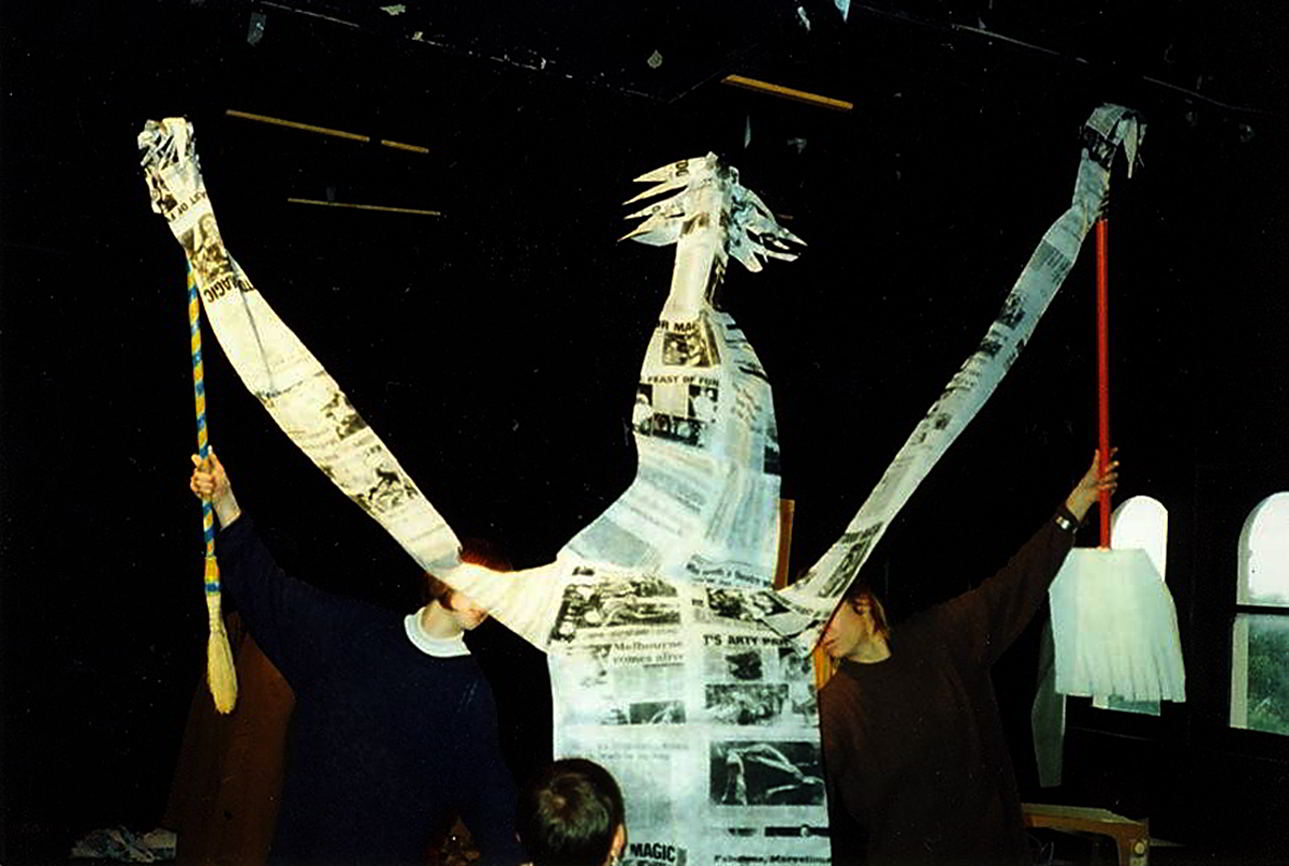

In the standard Leunig living room the harried 'she' figure attempts to cope with rubbish that accumulates as fast as it can be disposed of, windows that become barred prison walls, a headless husband whose newspaper suddenly grows arms and legs and rears up metres high, and a couple of hessian figures to perform a weird mummer dance of copulation and mutual mutilation.

The Design

Designer Laurel Frank and the company's puppetry magic have produced a strong, faithful piece of theatre that strikes a good balance between narrative momentum and moody, surreal detour.

Laurel Frank copied several of Leunig's cartoon elements in her sets and articulated images, enhancing their characteristics and dramatic capacity.

I aimed to focus the design on what the play was trying to say about the internal world, extending on the feelings that are found in Mary's drawings and bringing them into the broader environment.

One of the most evocative Leunig images recreated during the performance is that of a woman with a beautiful pair of wings who is obviously meant to fly in the sky. Instead she is held back by the clay on her feet, which she tries in vain to chip off. In the production it speaks reams about a woman's unfulfilled potential, and the memory of it is still haunting.

Powerful images using puppet techniques bring the anguish of a woman all too close to the bone. Images of child abuse with the use of dolls, domestic violence and cameos of the Gestapo leave no part of the smutty, boring, psychotic side of housewifery unexplored. The show was impeccable but the material seemed dated. The image of male as perpetrator of all womens' woes was unrelenting

Mary Leunig's world as interpreted by Handspan is feral domestica - a breathtaking work of visual theatre - with objects materialising and vanishing miraculously from the darkness. Furniture can suck a woman out of existence, the television set spits out dross, the lamp dances with the broom and the cat - well, it copes quite well with the existential mayhem. She, however, does not. She is being held siege by her own domestic life.

Responses

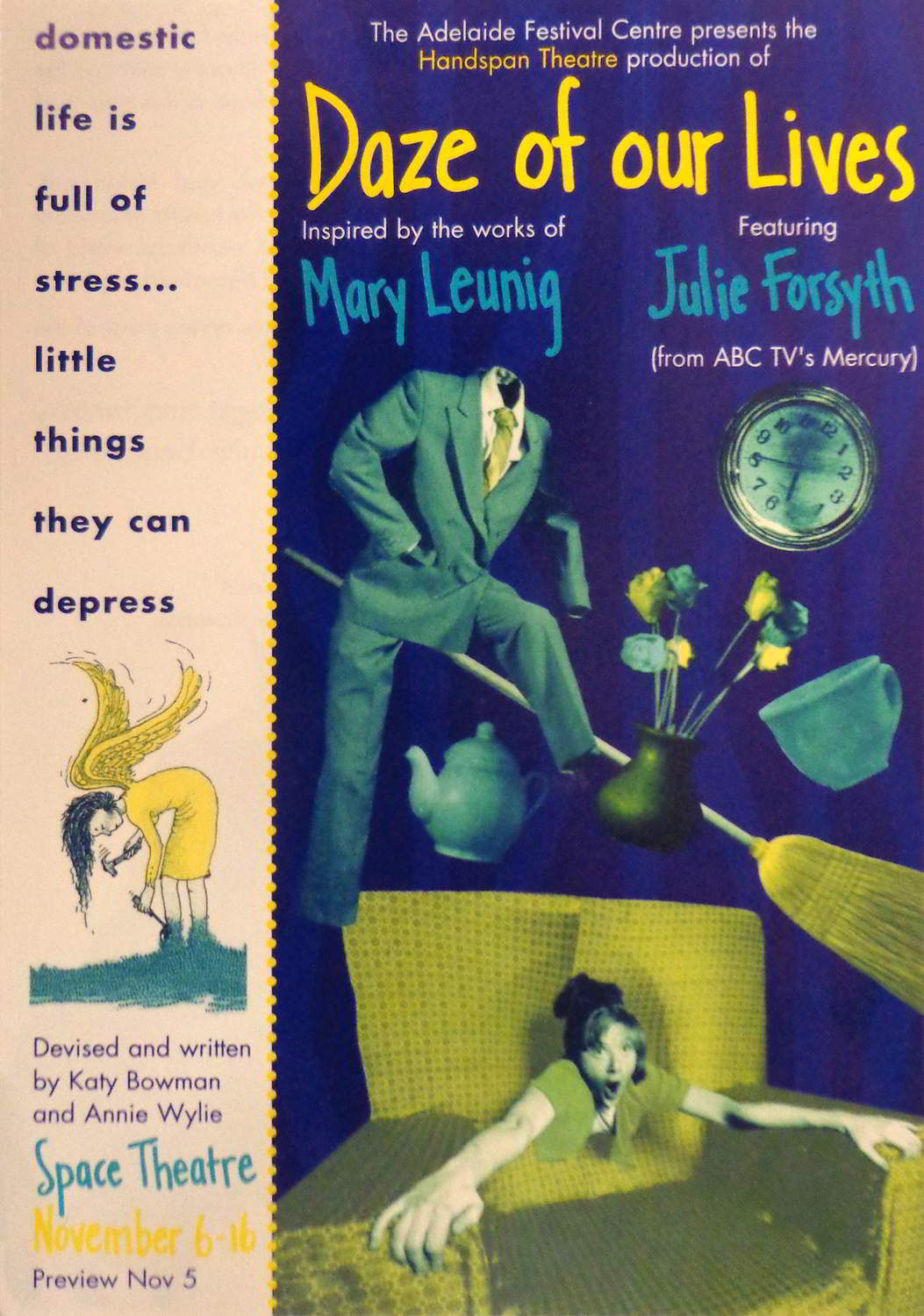

Following its Melbourne premiere season, DAZE OF OUR LIVES followed Handspan’s award winning production, Four Little Girls, to the Ibero-American Theatre Festival in Bogota, Columbia in 1996, and subsequently toured Sydney, Canberra (with Colette Mann in the role of She) and Adelaide.

The production was nominated for a 1995 Melbourne Green Room Award and critics were fascinated and predominantly enthusiastic.

Handspan have risen to the challenge of Leunig's work magnificently. If the show is not a complete success it is perhaps because its very project is incompletable: the translation of static drawing to a dynamic show, in which narrative cannot help but intrude, tends to dilute the fantasised, primordial nature of the drawings. It's an entrancing work that benefits from being watched with a more shifting, relaxed consciousness, more a drifting in and out, than is usual in a theatre piece.

This is theatre that doesn't tell the kind of story that has a beginning, middle and end. But it does tell a story of a housewife enmeshed, of her extravagant fantasies and desperate fears. Daze of Our Lives is grand visual theatre.

The production goes for a full 70 minutes without an interval and every moment is a joy to see. Not to be missed by anyone who enjoys good drama which lies outside the confines of much of our theatre today.

In this delightfully imagined production, Mary Leunig's celebrated images of domestic angst and fantasy are taken from the page and transformed quite beautifully by Handspan Theatre into a vivid and seamless stage dream.

Some reviewers, particularly in Canberra at the National Theatre Festival, were critical of the play:

Performance and puppetry have not coalesced into a gripping, exciting and dramatically cohesive entity.

In its swirl of images there is much that is clever, but without a clearly thought out and developed narrative, Daze of Our Lives is little more than a series of disjointed episodes.

With a tour of the work to Germany proposed for 1998, such responses 'prompted a structural review of the work to be carried out in 1997' according to incoming Artistic Director David Bell in the company's 1996 Annual Report. However, in the new programming and plans for the company, this did not eventuate.

Footnotes:

Creative Development company at Gertrude St. Studio, Fitzroy

From left, back row: Philip Lethlean, Winston Appleyard and Peter Neville ; centre: Katy Bowman, Annie Wylie and Laurel Frank ; front: Unknown, Clodagh Wylie, Avril McQueen, Unknown, Unknown

| Creative team | |

|---|---|

| Written & Devised | Katy Bowman and Annie Wylie |

| Dramaturg | Julianne O’Brien |

| Director | Annie Wylie |

| Assistant Director | Katy Bowman |

| Designer | Laurel Frank |

| Lighting designer | Philip Lethlean |

| Composer | Peter Neville |

| Performers | |

|---|---|

| Creative Development | Julie Forsyth, Clodagh Wylie, Winston Appleyard & Avril McQueen |

| Housewife | Julie Forsyth, Colette Mann (Columbia tour & Canberra season, 1996) |

| Puppeteer | Heather Monk |

| Puppeteer | Amber Parry |

| Puppeteer | Rod Primrose |

| Puppeteer | Michele Spooner |

| Production team | |

|---|---|

| Production Manager | Liz Pain |

| Stage manager | Penny Gutteridge (1995), Natasha Marich (1996) |

| Assistant stage manager | Joe Norster |

| Builders/ Scenic Artists | Katy Bowman, Cliff Dolliver, Rod Primrose, Rob Matson, Paul Newcombe, Tien Giang Tran, Katrina Gaskell |

| Publicity | Meredith King |

| Graphic designer | Rob Hall, Cornell Jenkins Hall |

| Photographer | Ponch Hawkes |

| Seasons | |

|---|---|

| 1995 | |

| 8 - 17 June | George Fairfax Studio, Victorian Arts Centre |

| 1996 | |

| 4th Ibero-American Theatre Festival, Bogota, Columbia. | |

| 7-17 August | Glen Street Theatre, Sydney, NSW |

| 4 -19 October | Theatre 3, National Festival of Australian Theatre, Canberra |

| 6-16 November | Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, SA |

| Total performances | Unknown |

| Total audience | Unknown |